Introduction to Interactive Proofs and Mina

/ 10 min read

This work is supported by a grant from the Mina Foundation

1. Introduction

This series will explore the fundamentals of interactive proofs and their practical applications. With a focus on how cutting-edge protocols like Mina leverages these concepts to achieve scalability, privacy, and efficient verification. Our goal is to bridge the gap between abstract mathematics and real-world implementations. Whether you’re well-versed in cryptography or new to the field, we aim to provide insights into how these mathematical ideas shape modern blockchain design.

2. Foundations of Interactive Proofs

Interactive proofs(IP) enable a prover to convince a verifier of a statement’s truth through structured interactions. These proofs are key to building efficient, scalable systems like Mina, where verification can be performed on lightweight devices without sacrificing security.

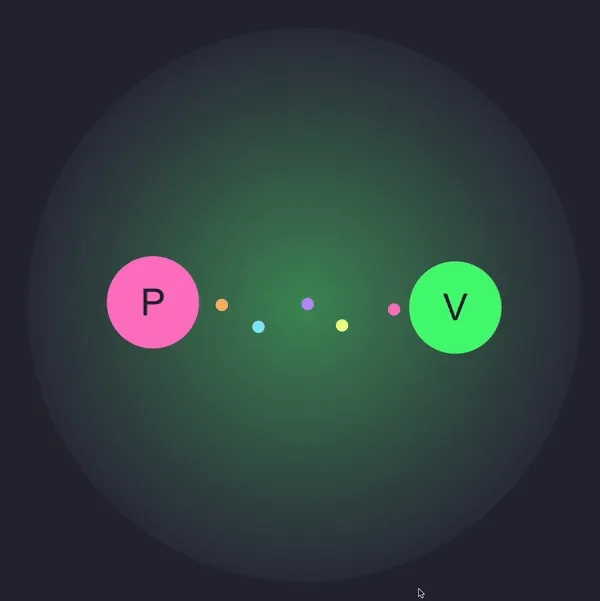

These proofs involve two parties: a prover and a verifier . The prover aims to convince the verifier of a statement’s truth through a series of interactions. Let be an interactive proof system for a language . Two fundamental properties define the strength of an interactive proof system:

Completeness: If the prover is honest and the statement is true, the verifier should always be convinced of the statement’s correctness. This ensures that the proof system behaves as expected when both parties follow the rules.

Here, and represent the random inputs to the prover and verifier respectively.

Soundness: If the statement is false, no prover (even a dishonest one) should be able to convince the verifier, except with small probability. Formally:

represents any potential prover strategy, including dishonest ones, and is the verifier’s random input.

Prover-Verifier Model and Basic Protocols

The structure of interactive proof systems can be represented as:

This representation shows the probability of the verifier accepting after rounds of interaction, where is the prover’s message in round , and is the verifier’s random challenge in round .

Example: Graph Isomorphism

Let’s illustrate these concepts with the Graph Isomorphism problem.

Definition

Two graphs and are isomorphic if there exists a bijective function such that for all , if and only if .

Interactive Proof

Let and be two graphs. The prover claims that and are isomorphic.

-

randomly chooses and a random permutation of the vertices of . sends to .

-

must determine which of or was permuted to create . sends its guess to .

-

accepts if , otherwise rejects.

Analysis

-

Completeness: If and are indeed isomorphic, can always determine the correct . Let be the isomorphism from to . When receiving , can check if or is an isomorphism to determine which graph was permuted.

-

Soundness: If and are not isomorphic, has at most a 1/2 probability of guessing correctly, as could have come from either graph with equal probability.

This protocol can be repeated multiple times to reduce the probability of a dishonest prover succeeding to an arbitrarily small value.

3. The Power of Interaction

Now we have a good background. Let’s zoom out a bit and discuss why the approach described above revolutionized our understanding of verification and computation. Their power lies in the dynamic exchange between prover and verifier, allowing for more efficient and expressive proof systems than traditional static proofs.

Historical Context: IP = PSPACE

A landmark result in the theory of interactive proofs is the IP = PSPACE theorem, proved by Adi Shamir in 1990. This theorem states that the class of problems that can be verified by interactive proofs (IP) is exactly the same as the class of problems that can be solved using polynomial space (PSPACE).

To grasp the significance of this result, consider that PSPACE includes problems thought to be much harder than those in NP. This means that interactive proofs can verify the solutions to a vastly larger class of problems than traditional NP proofs, highlighting the remarkable power of interaction.

Intuition Behind the Power of Interaction

The power of interaction stems from several key factors:

-

Adaptive Questioning: The verifier can ask questions based on previous responses, allowing for a more targeted and efficient verification process.

-

Probabilistic Verification: By using randomness, the verifier can check properties that would be infeasible to verify deterministically.

-

Reduced Communication: Interactive proofs often require less total communication than sending a full, static proof.

-

Resilience to Prover Strategies: The verifier’s ability to challenge the prover adaptively makes the system more robust against dishonest provers.

Connection to Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Interactive proofs laid the groundwork for zero-knowledge proofs, a powerful cryptographic tool. Zero-knowledge proofs allow a prover to convince a verifier of a statement’s truth without revealing any information beyond the validity of the statement itself.

This concept, introduced by Goldwasser, Micali, and Rackoff in the 1980s, has found numerous applications in cryptography and blockchain systems, including Mina’s zk-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge).

The idea that one can prove knowledge of something without revealing the knowledge itself stems directly from the interactive nature of these proof systems. This property is crucial for preserving privacy in various cryptographic protocols and blockchain applications.

4. From Theory to Practice: Interactive Oracle Proofs (IOPs)

Mathematical Intuition of IOPs

Let’s formalize the IOP interaction between a prover P and a verifier V:

-

Round-by-Round Interaction: For a statement x and a witness w, the interaction proceeds as follows:

Here, are the prover’s messages (oracle strings), are the verifier’s challenges, and are the verifier’s final queries.

-

Query Mechanism: The verifier’s queries work as follows:

Where denotes accessing the -th bit of the -th oracle string.

-

Verifier’s Decision: The verifier makes a final decision based on all interactions and query results:

The Random Oracle Model (ROM)

In the context of IOPs, we can define the Random Oracle Model as follows:

Let be a hash function modeled as a truly random function. In the ROM:

- For any new input , is chosen uniformly at random from .

- For any previously queried input , returns the same value as before.

Formally, we can represent queries to the random oracle as:

Where is either a new random value or a previously returned value for .

5. The IOP Revolution: From Theory to Practice

While Interactive Oracle Proofs (IOPs) and the Random Oracle Model (ROM) have been known to theorists since the 1990s, their practical implementation remained elusive for decades. It wasn’t until the 2010s that a series of breakthroughs transformed these abstract concepts into powerful tools for real-world applications, particularly in blockchain technology.

The Path to Practical IOPs

1. The Foundations (2010-2015)

The groundwork for practical IOPs was laid through several key developments:

-

2010: Yuval Ishai et al. introduced the concept of “Efficient Zero-Knowledge Proofs of Algebraic Statements,” bridging the gap between theoretical constructs and practical implementations.

-

2012: Eli Ben-Sasson, Alessandro Chiesa, and others published “Fast Reductions from RAMs to Delegatable Succinct Constraint Satisfaction Problems,” introducing efficient ways to convert complex computations into more manageable constraint satisfaction problems.

-

2013: The introduction of Pinocchio by Bryan Parno et al. marked a significant step towards practical, publicly verifiable computation.

-

2014-2015: Researchers refined techniques for arithmetic circuit satisfiability and developed more efficient probabilistically checkable proofs (PCPs), crucial building blocks for modern zk-SNARKs.

These foundational works set the stage for the rapid advancements that followed, addressing key challenges in proof size, verification time, and the complexity of setup procedures.

2. Groth16 (2016)

Jens Groth’s seminal work “On the Size of Pairing-Based Non-interactive Arguments” introduced a breakthrough in zk-SNARK construction:

- Achieved extremely succinct proofs (128 bytes) regardless of computation size.

- Enabled constant-time verification.

- Utilized a pairing-based approach, leveraging bilinear maps on elliptic curves.

- Key limitation: Required a complex and trusted setup phase specific to each circuit.

Groth16 became the gold standard for efficiency in zk-SNARKs, widely adopted in early blockchain implementations like Zcash.

3. Sonic and Marlin (2019)

These systems addressed the limitations of circuit-specific trusted setups:

Sonic (by Mary Maller et al.):

- Introduced the concept of a universal and updateable structured reference string (SRS).

- Allowed for a single trusted setup to be used for all circuits up to a given size.

- Enabled “helped verification” for improved efficiency.

Marlin (by Alessandro Chiesa et al.):

- Refined the universal SRS concept, improving on Sonic’s construction.

- Introduced a polynomial commitment scheme that became foundational for later systems.

- Achieved better proof sizes and verification times compared to Sonic.

These advancements opened the door for more flexible and scalable zero-knowledge proof systems.

4. PLONK (2019)

Developed by Ariel Gabizon, Zachary J. Williamson, and Oana Ciobotaru, PLONK (Permutations over Lagrange-bases for Oecumenical Noninteractive arguments of Knowledge) represented a major leap forward:

- Combined the universal SRS with a highly flexible constraint system.

- Introduced a novel “permutation argument” for efficient constraint satisfaction.

- Allowed for much simpler and more diverse circuit designs compared to previous systems.

- Achieved a balance of efficiency, flexibility, and security that made it widely adopted.

PLONK’s design enabled easier implementation of complex zero-knowledge applications, paving the way for systems like Mina’s zkApps.

6. Conclusion: From Theory to Mina

The journey from interactive proofs to modern zero-knowledge systems exemplifies how abstract mathematical concepts can evolve into powerful, practical tools. As we’ve seen, each advancement in this field has built upon previous work, culminating in systems like PLONK that offer a remarkable balance of efficiency, flexibility, and security.

Mina protocol stands as a testament to the real-world impact of these innovations. By leveraging the power of interactive proofs and their descendants, Mina has achieved what once seemed impossible: a constant-size blockchain of just 22kB, regardless of the number of transactions. This feat is a direct application of the concepts we’ve explored:

-

Succinctness: The extremely short proofs pioneered by systems like Groth16 enable Mina to compress its entire state into a tiny, verifiable package.

-

Universal Setup: Advancements from Sonic and Marlin allow Mina to use a single trusted setup for all its zk-SNARK applications, enhancing flexibility and security.

-

Efficient Verification: The constant-time verification properties of modern proof systems enable Mina to be verified on resource-constrained devices like smartphones and browsers.

-

Zero-Knowledge Properties: The privacy-preserving nature of these proofs underlies Mina’s ability to offer confidential smart contracts (zkApps) without compromising verifiability.

-

Recursive Composition: Perhaps most crucially, the ability to recursively compose proofs—verifying proofs within proofs—enables Mina to maintain its constant-size blockchain while processing an ever-growing number of transactions.

In future posts, we’ll delve deeper into how Mina harnesses each of these innovations. We’ll examine the specific role that PLONK and recursive SNARKs play in Mina’s architecture, explore the intricacies of zkApp development, and investigate how Mina’s unique approach addresses common blockchain scalability and privacy challenges.

As we continue this exploration, we’ll see how the theoretical foundations laid by interactive proofs have blossomed into a technology that’s not just revolutionizing blockchains, but potentially reshaping our understanding of trust, privacy, and verification in the digital age. The story of Mina is, in many ways, the story of turning mathematical theory into practical reality—a journey that’s only just beginning.

Reference

[CHMVW] Chiesa, A., Hu, Y., Maller, M., Mishra, P., Vesely, N., Ward, N.: Marlin: Preprocessing zkSNARKs with universal and updatable SRS.

[G] Groth, J.: On the size of pairing-based non-interactive arguments.

[MBKM] Maller, M., Bowe, S., Kohlweiss, M., Meiklejohn, S.: Sonic: Zero-knowledge SNARKs from linear-size universal and updateable structured reference strings.

[GWC] Gabizon, A., Williamson, Z.J., Ciobotaru, O.: PLONK: Permutations over Lagrange-bases for oecumenical noninteractive arguments of knowledge.

[PGHR] Parno, B., Gentry, C., Howell, J., Raykova, M.: Pinocchio: Nearly practical verifiable computation.